Mary Poplin (Ph.D. Education, University of Texas) began her career teaching in public schools. At Claremont Graduate University she developed the Masters Teacher Internship Program, directing it for fifteen years and simultaneously serving as Dean for two years. Her teaching and research examine learning and pedagogical theories, philosophy in education, worldviews, and research methods. Her research focuses on the inside of K-12 classrooms, most recently a five-year study of 31 highly effective teachers in low-performing urban schools. She has found that such teachers tend to be strict, determined, disciplined, and absolutely convinced that their students have enormous potential. You can visit Mary Poplin’s homepage here. An attractive summary of her recent work may be found here (see pp. 8 and 9).

Dr. Poplin, you are an educator. A popular stereotype of educators is that they invent impractical models of education that in the end don’t make a difference. Your goal from the start has been to make a difference. Exactly what sort of difference are you trying to make?

Well, some part of that stereotype may be deserved. In my recent research I could see that often what those of us in universities propose as best models of practice are not actually the ones being practiced by the most successful teachers in low-performing urban schools. Today these schools are my passion, to make my work contribute to closing the achievement gap between students who are rich and poor.

Much of your focus has been on K-12 education. Can you describe your own K-12 education? What was good about it and what would you have liked to see changed? You yourself taught for a time at the K-12 level? When was that and what was that like for you? What seeds were planted then that have influenced your subsequent academic work on K-12 education?

I believe I had a good basic education. I had strong teachers for the most part and learned all the basic skills and knowledge. If it could have been better, it might have been more classically oriented; the workout the more classical model gives your mind would have been very helpful [for “classical studies,” see below – Ed.]. I have and still do enjoy teaching. Most of my early teaching was with children with various disabilities. I think these experiences stimulated a desire to do more and a belief in the incredible potential of all human beings to enjoy life and contribute to others’ lives. As a teacher I always seem to be drawn to understanding how students’ minds work. Even now I stop and think what can I do here that will help students understand these principles more clearly, figure things out, and move toward understanding and making their unique contributions given their talents, interests, questions and desires to contribute. Thus my lifelong fascination has been with learning and pedagogical theories.

One of your interests has been special education. In fact, you edited The Learning Disability Quarterly from 1979-1984. How have you seen special education change in the last three decades? Special education at its worst is warehousing, at its best is transformational. Do you see both extremes? What is the best thing you currently see happening in the field of special education?

The best thing in special education is oddly enough the accountability movement that has forced us to raise our expectations. It has not always been done well, but I began to feel over the years that for many of our students, special education had become, as you call it, “warehousing.” However, I am not so sanguine that simply putting students with disabilities in regular classrooms is working as a strategy toward this goal. Since I worked in the field, it has become far more bureaucratic and legalistic, and rather than imagine new possibilities and work things out, we follow rules.

Describe your college and graduate work. How well did it prepare you for your present work? In what ways was your course of study less than ideal? What would have made it ideal?

Intellectually, I came alive in college. I loved the freedom to choose courses and to follow my heart into the discipline of education. I had an excellent experience in my graduate program at the University of Texas. We were all mentored, though it was admittedly narrow because special education is only one small part of a much larger picture. I had faculty who loved the debates, so we came to understand the range of views on the various issues. I think it made me a better thinker and researcher.

I often think we have university education upside down. Specialization is what many young people want first. At first you want a job, so you are not really paying attention to those critical first two years of broader study. Once you are working, then you want meaning and purpose; you are asking bigger questions. It was only later I began to wish I had paid more attention to my undergraduate core studies – science, literature, and history.

Your academic work has focused on both learning and pedagogical theory. How did you get interested in theories of learning and teaching? What are the major schools of thought here and what are their philosophical roots?

Being a teacher continually fuels my interest in the intersection between learning and pedagogy. There are a number of different schools of thought – direct instruction, constructivism, relational pedagogy, cultural proficiency, critical theory, and classical studies. Direct instruction emerges from empiricism and posits that the teacher’s role is to transmit knowledge in a systematic way giving attention to providing students with immediate feedback. The student learns by gradually acquiring a body of knowledge generally set forth and broken down in a curriculum.

Constructivism emerges from structuralism and suggests that students don’t acquire knowledge when they learn but rather construct meanings. The teacher’s role then becomes one of a facilitator rather than director. Constructivists seek to design activities and experiences that will lead students to search for knowledge and construct meanings related to the goals at hand (curriculum).

Relational pedagogy emerges out of feminist theory and posits that the relationships developed between teacher and student and among the students play a key role in their education. Here there is an emphasis also on intuitive learning and aesthetics; relational or womanist pedagogy represents a break from looking at learning as simply a cognitive activity.

Cultural proficiency is a model issuing from cultural studies, which presumes that students from different cultures need different approaches based on their cultural capital. Teachers first become culturally proficient themselves by understanding cultures and cultural manifestations and then adjust their instruction accordingly to make students’ experience more congruent with who they are and thus encouraging self-confidence.

Critical theory places a great emphasis on empowering the disempowered. The theory emerges from post-Marxist critical theory. Here everything in the curriculum is up for contestation and revision and students are taught to question deeply the existing (dominant) culture and to design projects to confront injustices. Teachers are seen as revolutionaries aiding young revolutionaries in a fight for justice.

Classical studies suggest that students need to engage with the world’s best literature, history, philosophy, science, math and religion in order to stimulate and shape minds capable of grasping great ideas, discerning fact from opinion, making moral and ethical judgments, thus contributing to the democratic republic.

Your educational research interests lie within the four walls of the K-12 classroom. First you had Project Voices from the Inside, which sold tens of thousands of copies. More recently, you and your team have spent several years in the classrooms of a number of high-performing teachers in very low-performing schools in some of the poorest neighborhoods in Los Angeles. What were you looking for and what did you find?

Our research team’s goal was to describe teachers who excelled inside poor and struggling schools in urban LA. I had for many years run a teacher education program that had as its goal educating teachers for urban schools whose students, statistically speaking, were less likely to reach the educational outcomes of their more affluent peers. These were the schools that often hired our new teachers. I was not certain how successful we were. We provided special training in second language instruction and English language development strategies and educated them in most contemporary theories and strategies. Still, I had no evidence that our teachers were any better than any others. So it finally occurred to me that there may be teachers in the least effective urban schools that were successful; and if we could know who they are and what they do, we might be able to educate teachers to be more effective.

We found there were such teachers; I would say approximately 10-20% of a school staff could fit into this category. So we poured over student achievement data to find the top performing teachers and observed 31 of them in nine K-12 schools in LA. We found they were strict, determined, disciplined, fairly traditional in their pedagogy, and absolutely convinced their students had much more potential than they were using. Interestingly, there was an overrepresentation of African American teachers, career changers, first generation immigrants and alternatively certified teachers in the sample.

I always tell people it took me 100 pages to write the report, but it took a fourth-grader only three sentences. We asked every student why they thought their teacher helped them learn so much and he wrote, “When I was in first grade and second grade and third grade, when I cried my teachers coddled me. When I got to Mrs. T’s room she told me to suck it up and get to work. I think she’s right, I need to work harder.”

[See “She’s Strict for a Good Reason: Highly Effective Teachers in Low-Performing Urban Schools” by Mary Poplin, John Rivera, Dena Durish, Linda Hoff, Susan Kawell, Pat Pawlak, Ivannia Soto Hinman, Laura Straus, and Cloetta Veney, www.kappanmagazine.org/content/92/5/39.abstract. Abstract: “A study of 31 high-performing teachers in low-performing urban schools found that these teachers had certain traits in common. They were strict; they taught in traditional, explicit ways; there was little time in their classrooms when instruction was not occurring; and they moved around the room helping their students. They used very few constructivist or cooperative activities. And they stressed particular virtues, including respecting self and others, working hard, being responsible, never giving up, doing excellent work, trying one’s best, being hopeful, thinking critically, being honest, and considering consequences. They strongly believed in their students’ potential and pushed them to achieve.”]

Jaime Escalante, the math teacher at Garfield High in East LA depicted in the film Stand and Deliver, died this year [2010 – Ed.]. Throughout the 1980s he was teaching high school students calculus and getting them to pass Advanced Placement tests in that subject at unheard of rates (especially for a low-income inner-city school like Garfield). Since he was just down the road from you, did you know him? Did you follow his achievements? Was the outstanding success he achieved a freak of nature? Or can that success be replicated, and if so how?

Sadly, I did not know Jaime Escalante personally, but I did follow his achievements. I don’t think everyone can be just like him, but he wasn’t a freak of nature. I think many of the teachers we studied were very similar. I certainly believe that all teachers can learn to think more as he did about his students’ potential and learn to use the intense methods he used to teach them to high levels of proficiency. It appears from my research that teaching students in blighted neighborhoods is not rocket science, but it does take a high level of commitment, determination, mental, emotional and physical strength, and a lot of just plain hard work. Add to this an enjoyment of students, hope for their futures, and a strong determination that the students are worth all this work and that this is your responsibility and even calling — then you have another Jaime Escalante.

You use a research methodology called “grounded theory.” Can you explain the method and how and why you came to choose it?

Grounded theory is an inductive research process for systematically gathering and analyzing data in order to describe, in its fullness, a particular phenomenon – in our case highly effective teachers in low-performing schools. In grounded theory, research participants are identified as the experts in the experience one desires to elucidate, and researchers start as “know-nothings,” learning first from the participants. Thus, grounded theory is a method for discovering what is there, not what we believe about it or how it exemplifies current theory. In our case, we wanted to know what do these teachers believe, what do they do, and who are they. The method yields conceptual categories after observing, sorting, analyzing, and comparing data (teachers’ actions and words; students’ actions, reactions, and words; and the researchers’ observations, memos, notes, insights, and team discussions).

While we were not so much looking to generate a single theory (as is most often the goal in Grounded Theory), we were interested in the systematic process of conceptualizing a large amount of data to produce an accurate picture of highly effective teachers. We used both quantitative and qualitative data, analyzing and comparing our findings to current and proposed policies and practices in the schools as well as current literature, theory, and practice in teacher education and professional development. The research process and team approach helped us capture a very large amount of data and avoid, as much as possible, tainting observations and interviews with our own assumptions about “good teachers” and our favored theoretical positions – what founder Barney Glaser calls “personal projections” and “theoretical capitalism.” The method of grounded theory was a perfect fit for what we wanted to research.

We hear a great deal about new laws that are impacting schools, which people seem mostly to love to hate. Can you shed any light on what’s happening with these laws? What is the big picture?

Ever since Brown vs. the Board of Education, educators in the United States have developed various theories and strategies to equalize educational opportunity. For fifty years we focused on strategies born in government and university offices. These strategies ranged from desegregation, Head Start, various compensatory education strategies, bilingual education, race and class based university admissions, school lunch and breakfast programs, as well as any number of favored pedagogical strategies, such as direct instruction, constructivism, critical theory, democratic education, multicultural education and project learning.

But by the end of the 20th century, there had been no real improvement when you looked at achievement. So when President Bush came into office, he brought with him policies that had begun under former Texas Democratic governor Ann Richards and continued under his administration. This new legislation focused not on new programs, strategies or methods but on outcomes. Thus the central measure of whether a school was successful with its students, particularly its most vulnerable ones, was whether the students improved on achievement measures. Prior to this time, federal projects were evaluated on whether the recipient did what they promised to do and conformed to the guidelines of the project, not whether they had achieved the results presumed to be affected. Well, you can imagine (and have seen) how this caused a seismic shift in the educational landscape, a necessary one, I believe.

There are a number of objections to NCLB and Race to the Top. Much of it questions the validity of standardized tests. Do tests tell us anything of importance? Are they reliable, valid? Is it fair to assess teacher performance on these scores? Certainly tests don’t tell us everything, but they do reveal basic achievement levels and it is the most reliable and valid tool we currently have. We saw in the data that high-performing teachers’ students do well year after year on these measures while some other teachers’ students perform poorly year after year, even losing whole levels of academic achievement. I personally believe the issue of achievement is so critical to future life opportunities of a child or adolescent that this is an issue that, at its core, embodies the struggle for justice. We cannot afford to separate issues of justice from accountability.

The other major argument against NCLB and RTT has been that the federal government has mandated but not funded these new regulations. The federal government in the U.S. has never had responsibility for education as a whole. Instead, states do. But it has acted in oversight to stimulate necessary changes, particularly for justice, such as in the case of students with handicaps, equity in sports, and students who live in poverty. In fact, President Bush doubled the funds to education and President Obama may do the same. This radically increases federal contributions to states even though, of course, it will not pay for everything. It requires schools and teachers and those of us in education to think and act differently.

If you had to advise a college senior who wants not only to get a Ph.D. in education but also to use that degree to substantively improve education in the United States, where would you send him or her?

I might suggest they get involved with something like Teach for America first. It is a very good teacher education program with good results. It provides an opportunity for the brightest young college graduates to experience teaching in the most challenged schools. They might also try working in a charter program such as Knowledge is Power Program or even somewhere like the Harlem Children’s Zone. Then they would know if this were to be their life’s work.

SuperScholar recently interviewed Christopher Langan, who lays legitimate claim to having the highest IQ of anyone in the United States (estimates of his IQ range between 195 and 210). Far from thriving in K-12, he felt alienated, unchallenged, bored. After an unhappy year in college, he never returned to the academy. Does his situation surprise you? What can educators do to help students like him?

From what I read in his interview, I’m honestly not sure universities would be very helpful to Christopher Langan, except as he points out in terms of credentials. I believe he is right about the unfortunate monopoly universities hold on the intellectual world. His interests and work are so broad that he also challenges the university’s strict disciplinary boundaries as well as its ideological boundaries. Clearly, he is doing his work despite the odds. It appears he has an incredible capacity to overcome adversity. He rightly notes the Internet is an advantage here. What motivates him and carries him through are things beyond what one finds taught in most university programs.

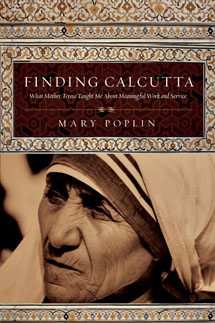

In 1996, you spent two months in Calcutta working with Mother Teresa and the Missionaries of Charity. Why did you go there and what did you learn?

I went to try to find out what she meant when she said their work was religious work and not social work. What I found is that they work from a very different worldview than most of us can understand from our secular education. I wrote a book on my experience while there, Finding Calcutta. That story ends with the question of whether secularizing the university actually limited its whole-hearted search for truth. Simply put, Mother Teresa and the way she lived her life cannot be understood from the worldviews currently dominant in the university.

I went to try to find out what she meant when she said their work was religious work and not social work. What I found is that they work from a very different worldview than most of us can understand from our secular education. I wrote a book on my experience while there, Finding Calcutta. That story ends with the question of whether secularizing the university actually limited its whole-hearted search for truth. Simply put, Mother Teresa and the way she lived her life cannot be understood from the worldviews currently dominant in the university.

You’ve now been a classroom teacher, professor, director of a graduate teacher education program, dean, and now you are back teaching doctoral students and conducting research – From your experience over the years, what advice would you have for your field as a whole?

We must stay focused on accountability; there must be some measurable results to which we are willing to hold ourselves responsible. Those of us in the university need to be much more responsible and accountable also. We need to become more diligent about checking our theories with reality (which is where we started our conversation). We have to become more scientific and less ideological; I saw how children’s futures depend on it.

Research is about asking interesting questions and finding innovative ways to answer them. What are the next questions on your mind that you plan to research? Where will you be looking for answers?

That’s an interesting question. I am still very interested in worldviews and how the various theoretical orientations of learning and pedagogy emerge from different assumptions. Also, I would like to explore is why knowledge has so little effect on our actions. For example, many of us know that smoking, drinking or taking drugs has a deleterious effect on us, but that does not appear to be sufficient to change our behavior. I suppose I’m headed into that murky area of epistemological questions like, What does it mean to know, understand, and discern? How do knowledge, understanding and wisdom differ? Such questions, of course, raise the further questions, What does this mean for teaching and learning, and for schools and universities? I’m headed for more study.